Master plans and comprehensive plans are both important planning documents, yet they are different tools that fulfill different needs for a city.

While a comprehensive plan is an essential first phase in a municipality’s planning process, it is typically used to broadly state a community’s goals and offer a baseline for regulation. For example, it may offer advice for how the city should grow, but it gives few specific ideas for actual development.

"State law requires a comprehensive plan. It’s a document that sets future land use of a community. But it’s very broad," said Eric Budds, deputy executive director of the Municipal Association of South Carolina.

All municipalities that have planning and zoning regulations must conform to the state Comprehensive Planning Act, which requires a comprehensive plan to give planning commissioners, municipal officials and residents the opportunity to map out the community’s future. To ensure the plan continues to reflect the community’s values, the council must re-evaluate it every five years and update it every 10 years.

"A comprehensive plan looks at jurisdiction-wide issues," said Robert Moody, senior planner with the Catawba Regional Council of Governments in Rock Hill.

State law also defines nine elements that a comprehensive plan must address, including population, economic development, natural resources, cultural resources, community facilities, housing, land use, transportation and priority investment.

The other type of planning document cities use is a master plan. "You can’t get specific in a comprehensive plan. Cities choose to do master plans to focus on a specific area and to guide development in a much more specific manner," Budds said.

Generally, the tighter the scope of the master plan, the better and more useful the plan will be. In smaller cities, an entire downtown district could be addressed in one plan, while larger cities might need a plan to focus on a specific neighborhood.

Cities can do master plans in-house, possibly contract with their council of governments or hire an outside firm to develop the plan. The approach would depend on the municipality’s size and needs.

Randy Wilson is president of Community Design Solutions in Columbia, a firm that develops master plans for cities. He said there are two main benefits from master plans: A city receives a definite target to shoot for as it develops over the next five or 10 years; and the plan makes it clear what a city should not do.

"Our cities are so strapped for cash that there is a tendency to say yes to all economic opportunities. But if you put the wrong use in the wrong location, it’s there for a generation. It’s imperative that you get it right," he said.

Wilson offered these best practices for cities getting ready to take on a master plan:

- Involve the public. If a plan for a downtown district or a specific neighborhood affects citizens, city officials should encourage their voices. Often, people who are going to be directly impacted by the plan can offer strong ideas.

- Make the plan holistic. A master plan should not only address the buildings and physical structures in a town or district; but it must also include market analysis, branding and marketing, planning and design, and implementation strategies, including identifying possible funding sources.

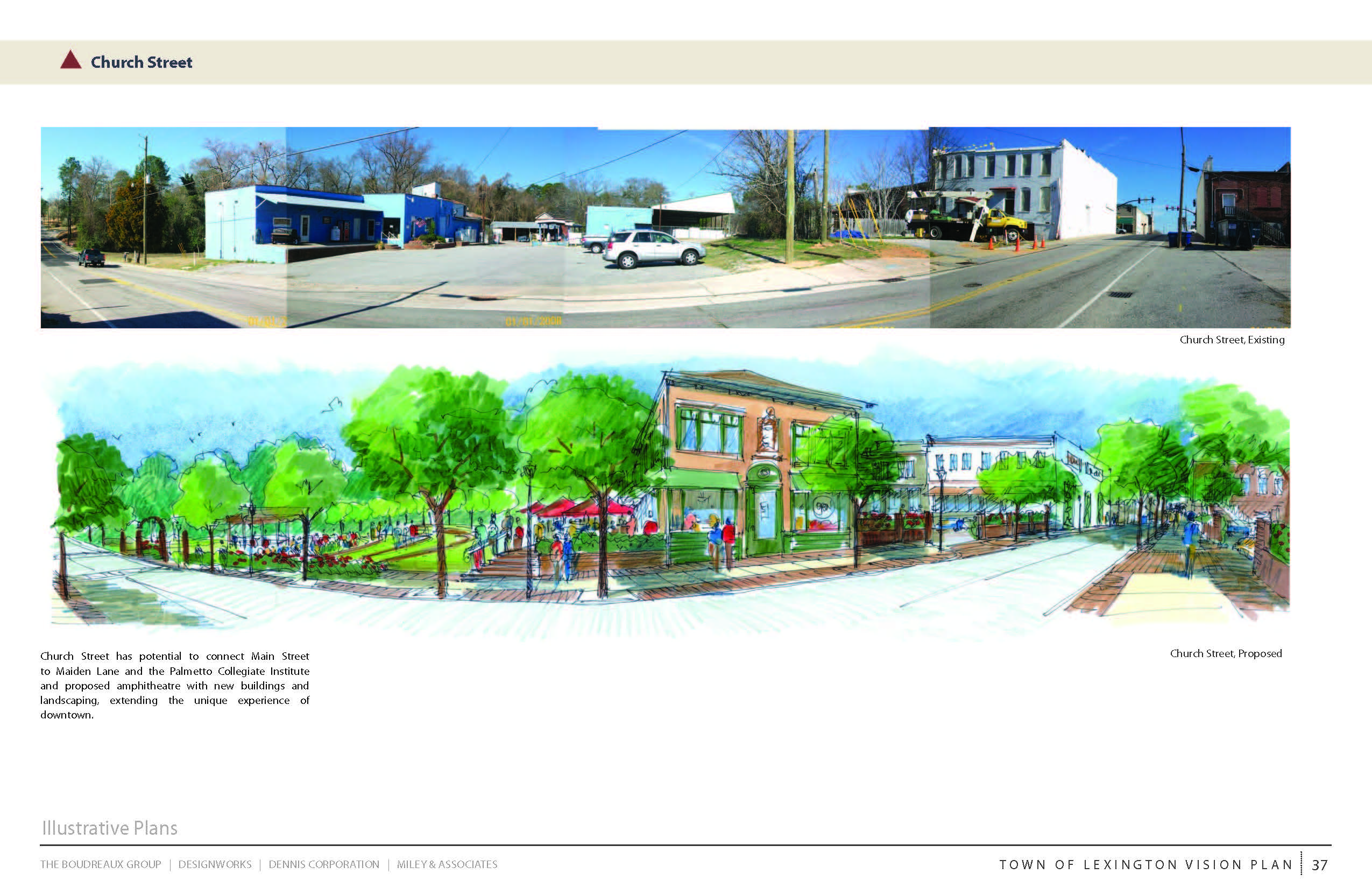

- Paint a picture. A master plan needs to be "highly illustrative," casting a vision and showing the city leaders and residents a picture of what can be accomplished.

Wilson said the cost of a master plan depends on its size and scope. A small, more rural town should expect to pay an outside consulting firm about $35,000 to $60,000 for a master plan, while a large urban city could expect to pay $75,000 to $200,000, he said. A smaller-concept plan would take about two to three months to complete, while a full plan will take four to eight months.

Both the master plan and the comprehensive plan are critical to a city’s success. The key is using each appropriately.